On the night of the 7/8th September 1940, an unassuming warehouse in Arnside Street, Walworth, south London, was hit by German incendiary bombs. It seems highly unlikely that the German bomb-aimers had anything against this particular warehouse, but their efforts that night succeeded in robbing future generations of historians of rich sources of information about their British army ancestors. For the warehouse contained soldiers’ service records of the First World War – officers’ and men’s records – and millions of other documents besides, and in the ensuing fire which tore through that warehouse, millions of papers were lost.

That anything survived at all was a miracle, and what was salvaged was often badly damaged as a result of fire, smoke and water from firemen’s hoses. Officers’ papers were stored in a part of the warehouse that was completely destroyed, but some other ranks papers were spared – estimates normally settle around 35% to 40% saved – and it is these remaining papers which today from part of the collection catalogued by The National Archives in series WO 363 and known today as ‘the burnt documents’.

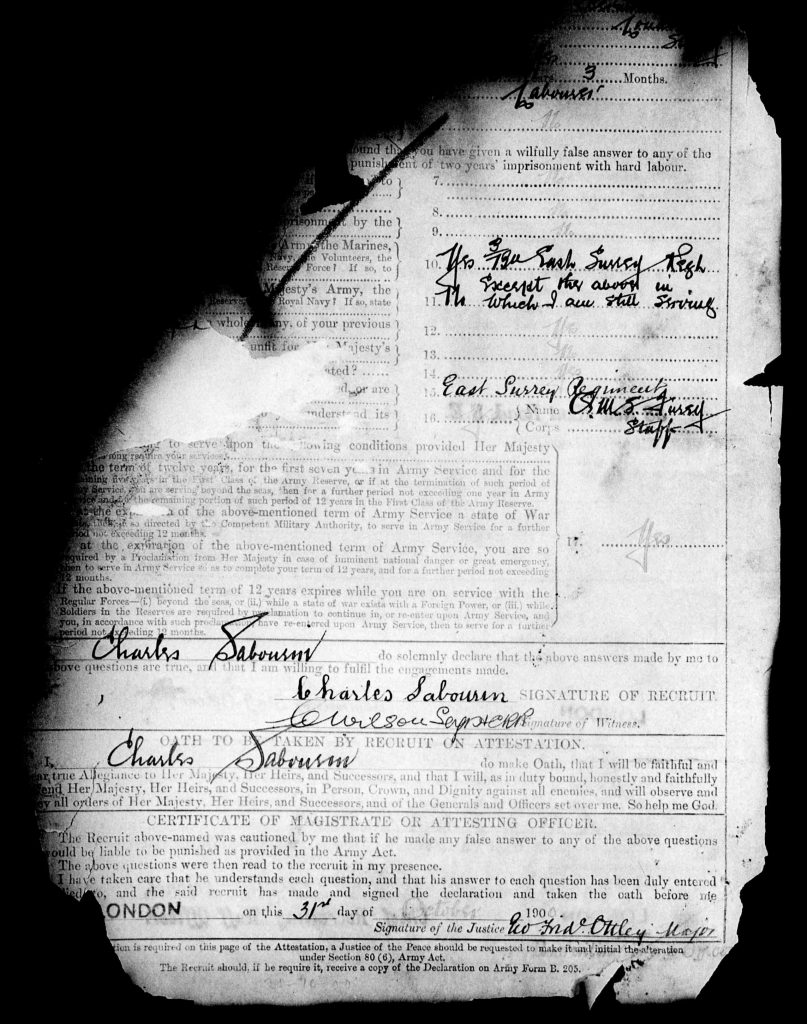

Charles Sabourin’s papers in WO 363 are a good example of a typical burnt document. The original papers have now been removed to safe storage, but The National Archives did film what was left and these microfilms were subsequently digitsed and published first on Ancestry.com and latterly on Findmypast.co.uk and elsewhere. In the image above, the charred edges of the document clearly demonstrate fire damage, and other papers also exhibit water damage. Nevertheless, “better than nothing at all” is a phrase that springs to mind and in Charles Sabourin’s case, he also has papers in WO 364 which either repeat information or fill in gaps found in WO 363.

The range of documents to be found in WO 363 is extensive, with attestation papers (various army forms), medical history forms (Army Form B.178), and casualty form active service (Army Form B.103) arguably the most useful to the modern day family historian. The series not only contains records of men who survived the war, but those who lost their lives during the conflict. For these men, where they survive, Army Form W.5080 can be a treasure trove of information as it records names, ages and addresses of close living relatives.

For more information of the types of forms to be found in WO 363 have a look at my Army Forms and Attestations blog which lists various forms and gives examples of what these look like.

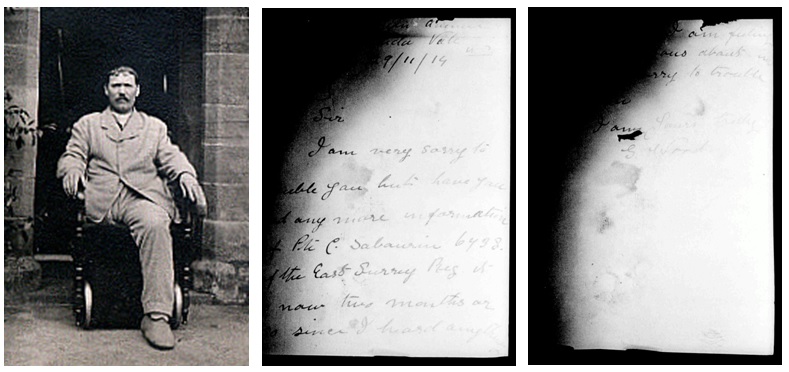

Charles Sabourin’s WO 363 file also contains correspondence from his worried family after he’s been reported missing. In actual fact he’d been severely wounded on th opening day of th Battle of Mons on th 23rd August 1914 and had been captured by the Germans. Later, he would be repatriated by the Germans and would spend time convalescing in Sussex before returning to his family.

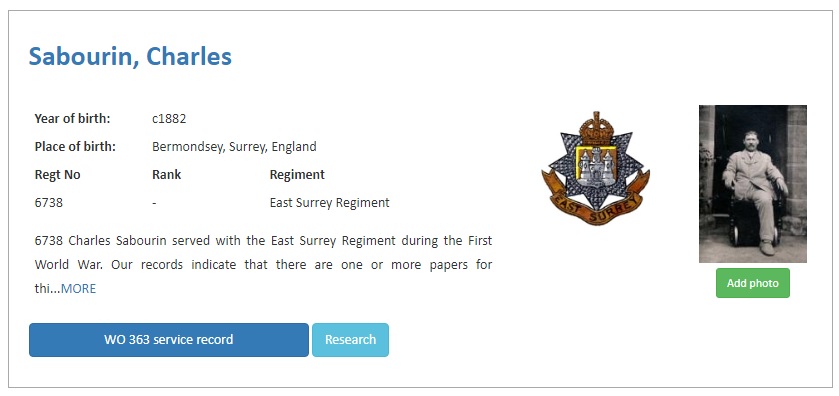

You’ll find links to records in WO 363 on British Army Ancestors rsearch results. Here’s what Charles Sabourin’s record looks like:

Clicking on the large blue button link will take you to Charles Sabourin’s record in WO 363 on Findmypast, one of close to 3.6m records in this one series alone. Findmypast has indexed far more records in WO 363 and WO 364 than its competitors and so I always use this as my default family history website when looking for these records. If you don’t already have a subscription to Findmypast you will find yourself presented with a paywall when when you wish to view these images, but all sites offer free trials and incentives.

Remember too, that whilst these records in WO 363 are billed as service records from the First World War, many of these men had extensive service before the First World War and continued to serve from 1914-1918. Some of the records in WO 363 go back as far as the 1870s!

So to recap:

WO 363 contains often very badly damaged documents of NCOs and men only.

WO 363 contains records of men who survived and those who lost their lives during the First World War

WO 363 may also contain records of men who were serving soldiers when Britain went to war in 1914.

The Burnt documents. Challenging, difficult to read, frustrating, but so essential. That anything survived the fire at Arnside Street on the 7/8th September 1940 is a miracle, and many of the so-called 'burnt documents' bear witness to the ferocity of the fire. Millions of documents were lost and so if you do find a soldier's papers in this series, you're doing better than many.

Fire and water damage have conspired to make many documents difficult to read. Some documents also show signs of having been 'tidied' with scissors, the burnt edges trimmed. In many cases, additional information would have been lost in this 'trimming' process.

Make the most of the burnt documents by first downloading all relevant pages. Findmypast has indexed more records in WO 363 than its competitors and so you are more likely to find a soldier's records here - even though that record may be just a single fragment - than elsewhere. Download all the relevant pages and then manipulate hard-to-read images using programmes such as Paint, Photoshop or Picasa. Try reversing out the colours so that you view the image as a negative. This can often help to reveal 'hidden' text. Also adjust contrast and brightness. The image you download is the best it's going to be. The original documents will never be released to the General Public and so make the most of what you have.

If you need assistance with interpreting papers in WO 363, I offer a full research service and will be pleased to 'translate' files page by page. See the Research page on this site for more information. Images on this column are taken from the David Knights-Whittome collection which has been thoughtfully conserved and re-published by Sutton Archives. The Past on Glass collection can be viewed on flickr. David Knights-Whittome owned photographic studios in Epsom and Sutton and his archive contains images of hundreds of men who served with the Public Schools battalions of the Royal Fusiliers during the First World War.